|

|

Screenmancer Exclusive presents

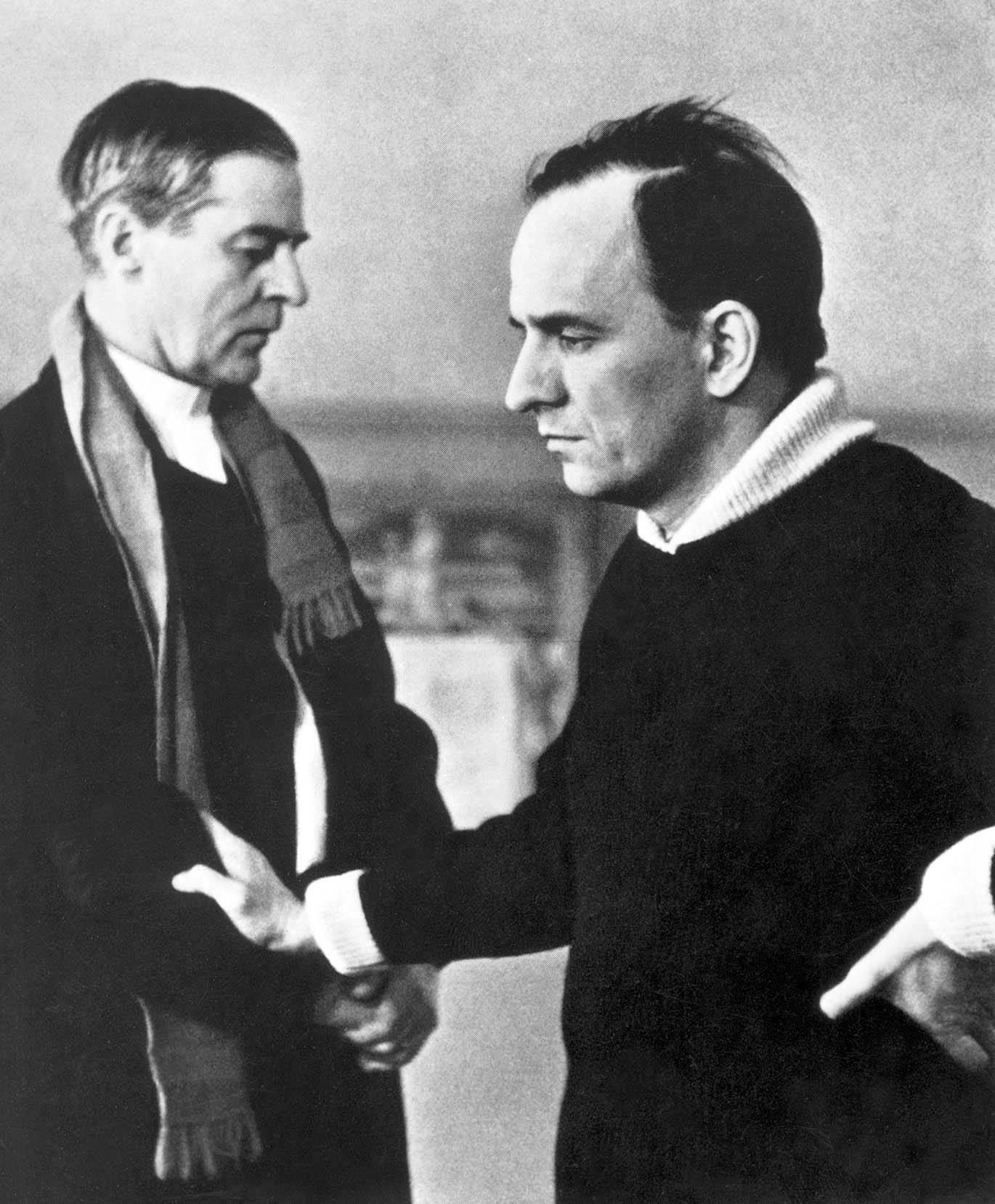

Photo Credit: Ingmar Bergman Foundation

Ingmar Bergman Face to Face:

An Official Tribute

by Jon Asp, Editor in Chief

Ingmar Bergman: 14 July 1918 - 30 July 2007

The film and theatre director Ingmar Bergman has died at the age of 89. Bergman began his professional career in the theatre at the end of the 1930s. He was to revolutionise the theatre many times over, and it remained his greatest and constant passion. Yet it is as a filmmaker that he became best known to the world.

Ingmar Bergman is not only one of the greatest ever Swedish artists and film directors, but one of the world's leading filmmakers of all time, who ranks alongside other giants such as Kurosawa, Ozu, Tarkovsky, Godard and (the late) Antonioni. At a national level his influence is beyond compare. If the silent filmmakers Sjvstrvm and Stiller brought about the first Golden Age of Swedish cinema in the 1920s, the second such age was surely engendered in Bergman's collected works. Beginning in the 40s, and especially from the 50 onwards, he put Sweden on the world cinema map once again, ensuring that it remained there for the next half century.

As the 24 year-old screenwriter for Alf Sjvberg's much-discussed 1944 film of school life Torment, Ingmar Bergman made a prominent debut in the cinema. His directorial debut Crisis came soon after, living up to its name in more than one respect: it bombed with critics and audiences alike; causing Bergman to be fired by Svensk Filmindustri. (All was later forgiven, however, and he was allowed to return).

His first success as a director came with his sixth feature, Prison (1949), significantly the first of his own films for which he wrote a completely original screenplay. "For the first time in 25 years Sweden is once again at the developmental cutting edge of world cinema", wrote 'Robin Hood', the veteran film critic of Stockholms-Tidningen. The reviewer probably had in mind the various themes and elements that Bergman was to develop further, not least in his more experimental works of the 60s.

Thwarted ambitions as a writer and the constraints of making films in Sweden at the time left their mark on much of the director's work of the 40s: well-written yet occasionally overly literary pieces, often with overt overtones of melodrama and compromise. His real successes came during the 50s, based around a group of actors who doubled up for the director. The actors that Bergman schooled at Malmv City Theatre during the season, including Ingrid Thulin and Max von Sydow, were used in his films during the summers, an arrangement that Bergman honed to perfection.

His first international success (although somewhat retroactive) came with Summer Interlude Sommarlek (1951), a work that should be regarded as one of his most artistically significant films. In it, he was greatly assisted by Gunnar Fischer's expressionistically charged images and by his leading actress, Maj-Britt Nilsson, whom he chose to portray the ballet dancer Marie from her aspirations as a teenager through to her subsequent disillusionment 13 years later. Bergman's predilection for flashbacks was already well known, but never before had me managed to use them to such consummate effect.

His real breakthrough, however, came with Smiles of a Summer Night, a comedy set at the turn of the century. The film picked up an award in Cannes in 1956 and not only cemented Bergman's international reputation, but more significantly allowed him much greater creative freedom. "Since the success of Smiles, nobody has ever interfered with my work: I've been allowed to do what I wanted." It took him more than 15 films to arrive at this point, clearly illustrating that a strong desire to work, patience and high productivity all played an important part in the director's genius.

If Strindberg was Bergman's lodestar in the theatre, Victor Sjvstrvm occupied the same position in film. On countless occasions Bergman confessed his devotion and debt of inspiration to these two grand old men of Swedish culture. The year of Bergman's death, 2007, is something of a coincidence in itself; since it comes exactly 50 years after two of his most successful films of all. With 1957's Wild Strawberries, in which a fading Victor Sjvstrvm is flanked by the rising star of Ingrid Thulin, and The Seventh Seal, the symbolic drama that is one of the world's most quoted films, Bergman's success became all-encompassing.

Bergman won his first Oscar for The Virgin Spring (1960), closely followed the next year by another for Through a Glass Darkly, both for best foreign language film. Through a Glass Darkly was also the director's first major collaboration with Sven Nykvist, who made important contributions to the new directions that Bergman's filmmaking was to take, culminating in Persona (1966).

For a number of reasons, the 70s were not quite so productive or successful. Nonetheless it was the decade of Cries and Whispers, Scenes from a Marriage and his universally acclaimed television production of Mozart's opera The Magic Flute . During his period of exile in Munich, Bergman made the films Autumn Sonata, The Serpent's Egg and From the Lives of the Marionettes, each of which had a mixed reception. His return to Sweden and genuinely Swedish film was, on the other hand, altogether more successful. Fanny and Alexander (1982) not only won four Oscars, but assured Bergman of a special place at the heart of Swedish culture. As recently as 2003 he directed the television film Saraband, a somewhat unexpected yet nonetheless scintillating comeback, shown in cinemas around the world, where it was praised more highly than in his native country.

Recurrent themes in Bergman's film universe are imagination, doubt and damaged relationships, examined in flashbacks (To Joy), mirrors (Through a Glass Darkly), masks (The Face, Persona) and unusual light (Winter Light). Despite a range of styles, repetition appears to be both a means and an end in itself, at worst exasperating, almost always rewarding and at best breaking new ground.

Bergman's international successes of the late 50s inspired Swedish cinema on several levels. People slowly began to realise that artistic merit could actually pay dividends. The National Film Agreement appeared under the guidance of Harry Schein in 1963 (Bergman was probably his spiritual deputy), an agreement that paved the way for other Swedish directors to step onto the world stage: (such as) Bo Widerberg, Jan Troell, Vilgot Sjvman, Mai Zetterling and later Roy Andersson. Paradoxically enough, many of these filmmakers often object to the praise lavished on Ingmar Bergman's body of work.

Despite his dominance in his native country, Bergman never achieved the same recognition in Sweden as abroad, a fact pointed out on the day of the director's death by the author and playwright, P O Enquist, who worked with Bergman and has been inundated with tributes to the director from many of his international colleagues. Godard has noted that " Summer with Monika is the most original film by the most original of filmmakers". A poster for that film can be seen in the background for Truffaut's The 400 Blows. Eric Rohmer has declared The Seventh Seal the most beautiful film ever made. Bergman himself never declared an allegiance to the French New Wave, Godard least of all. He was more impressed by the more classically educated Marcel Carni instead. Yet Bergman's influence on the world of film, especially the nouvelle vague, has been enormous. The archetype for this inspiration could easily be the figure of Monika herself, immortalised by Harriet Andersson, the hiros ordinaire in everyday clothes who has provided the model for numerous main characters in the French new wave, a figure often at odds with the conventions of society.

Often regarded as a director in the classic tradition, sometimes negatively described as 'literary', 'theatrical' and in some respects 'conventional', it is only right to remember that Bergman was also an experimental filmmaker. This is most evident in his films from the 60s and 70s, where the lighting of Winter Light and the use of colour in Cries and Whispers are just two examples of completely unique exercises in cinematic style.

The greatest misapprehension which his detractors, many Swedes among them, never cease to proliferate is that Bergman is relentlessly gloomy. An anguish ridden director possessed by demons, a middle class elitist and a womaniser who neglected his own family � how many negative characteristics does one person need to be unpopular in his native country? Bo Widerberg accused Bergman of making 'vertical' films, of not reaching out to the broad masses, an interesting observation that demands closer scrutiny.

Bergman's elitist reputation was somewhat assuaged by Scenes from a Marriage and the more populist elements of Fanny and Alexander, and his occasional appearances on television and in popular radio programmes of recent years seem to have secured him a place in hearts of the Swedish people. This is more true, however, of Ingmar the man than of Bergman the artist, whose works still appeal to very few of his fellow countrymen.

Abroad, his reputation for gloom has possibly had a more positive effect, contributing to the mythmaking around Bergman and his demons, the apt inheritor of a mantle passed down from Swedenborg, Strindberg, and Dagerman, and handed on in our own times to the playwright Lars Norin, among others.

Much of this over-simplification probably stems from the recurring themes of God and death in Bergman's films, symbolised most notably in The Seventh Seal, with its Grim Reaper and Dance of Death, amplified and further explored in his pared-down films of the 60s, of which Winter Light, The Silence and not least Persona have come to be regarded as being among the director's greatest films of all.

But the fact remains that Bergman consistently laced many of his works with humour and wit. Farce and burlesque The Devil's Eye and Now About These Women), dark melodramas (from Prison to Journey into Autumn), Hollywood style marriage comedies ( Waiting Women and A Lesson in Love), which in their brilliance and spirit are often comparable with his breakthrough film, the popular comedy Smiles of a Summer Night.

Even in the most gloomy Bergman films, such as Scenes from a Marriage and the stiflingly intense Saraband, comedy is never far away. In the midst of all the jealousy, mental torture and perversion, the cynic par excellence, grandfather Johan, played by Erland Josephson concludes: "A good relationship between a man and woman is made up of two parts: good friendship and strong sexual attraction."

It's high time to laugh at the wretchedness of it all. And above all, it's high time to update our impression of Ingmar Bergman's body of work, which not only covers a lifelong and fruitful interchange between the stage and the film studio, but also many of the subjects and themes worthy of a true master: happiness and sorrow, dreams and reality, life and death.

SCREENMANCER thanks JON ASP - chief editor,

Ingmar Bergman Face to Face - for his contribution

|

|

|